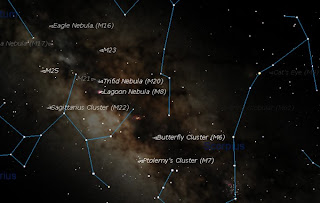

Each month I will describe sights of interest in the night skies of South Carolina. These sights will be broken down into three sections; what you can see with the naked eye, with binoculars, and with a small telescope. The best time to view the night sky is at and around the times when the Moon is not visible, what is known as a New Moon; which will occur this month on December 5th. For December, your best viewing nights will be from December 1st through December 11th. The Star chart below is set for Florence, SC on December 15th at 9 pm.

Star Associations:

Again this month, I was asked another difficult question. A recent news article stated that the first planet was found in orbit around a star from another galaxy! It is extremely difficult to find planets circling nearby stars, so how can we find a planet around a star from another galaxy? The operative word here is “from” and not “in” another galaxy. In most of the news reports of this discovery, the news article did clear up the matter by stating the that star in question was indeed in our own galaxy, but this particular star was captured billions of years ago from a galaxy outside of the Milky Way. So now the real question is how does one know that a star in our Milky Way came from another galaxy?

To answer this question, it is necessary to discuss the “proper motion” of stars. Proper motion is the change of position of a star in relation to our solar system. The general concept of our Sun and other nearby stars is that we are all spinning together around the Milky Way galaxy; somewhat like leaves floating along on a river. However, many stars have some type of angular momentum in relation to us, see image below.

Remember, all the stars in the image are spinning around the Milky Way galaxy with us, but some are also moving at various angles and speeds in relation to our solar system. The cause of this erratic motion was most likely due to gravitational interaction of these stars with other stars sometime in their lifespan.

Expanding on this concept, astronomers have found that several stars in certain regions of space sometimes have a similar speed and angle of proper motion. It was also noted that they have a similar age. These star groups are called “star associations,” and it is believed that these stars were all born in a similar region of space, and are slowly moving away from their place of birth.

A well-known star association is the Perseus Association. Simply go out this month and aim your binoculars at the main star in Perseus, Mirfak, and the stars you see around Mirfak are members of the Perseus Association. Also note if you move your binoculars slightly off in any direction, you will see much less stars in your field of view. Using the chart below, you can easily find Perseus and Mirfak by using the constellation Cassiopeia (“W”) as a guidepost. This image shows the sky in mid December facing east and looking almost straight up. Also note that Mirfak is about halfway between Cassiopeia and the Pleiades.

There is another star association that is very easy to see; just look at the Big Dipper. Five of the stars of the Big Dipper are part of a star association. Only the two end stars Alkaid and Dubhe are not part of the association. The other five stars are all moving at the same speed and in the same direction.

This means that in the distant past, the Big Dipper didn’t look like a dipper, and therefore in the distant future, it will not look like a dipper. The green arrows on the image below show the proper motion of the stars in the dipper.

So if you have been following my discussion, you are likely wondering what about the news item above, and how did they know that the star and planet were from another galaxy? Sometimes the proper motion of star associations in addition to moving in the same direction are also moving much faster than common associations and contain many more stars. This type of association is known as a “star stream.” The only explanation for a star stream is that in the distant past our Milky Way galaxy captured stars from another galaxy and we are seeing this stream of captured stars as they pass through our Milky Way. The star mentioned in the news article with a planet revolving around it was a member of a star stream. The artist’s sketch below tries to give an idea of how star streams may be associated with our galaxy.

To all my readers: Have a wonderful Christmas and a Happy New Year.

Naked Eye Sights: Check out the Geminids meteor shower, which will peak on the evening of Dec 13th, and into the early morning of the 14th.

Binocular Sights (7 to 10 power): The Perseus Association.

Telescope Sights (60-100mm): Jupiter is still the best target this month.

See you next month!